Stucco and Suture

by Ricky Novaes de Oliveira

Construction. Solder sparks orange, building. A vision— Train rush. Playlist pause. Crosswalk, waiting, corner of my eye, Ten years later, thirty-three miles away, and I think I see you— Vanish. I just wish we could tell you over (family dinner! vacation! a smoke!) and over again How lucky this family is to build anew without you (though your love still lingers)— It’s complicated. We moved away right before you passed Away from that house of stucco and suture, where you were sick and sedated, needing quiet. Where we played house as loud as wouldn’t wake you. There, trying to stitch your crumbling sadness covered us all. Ten years later, thirty-three miles away, and I do see you In the cracks, in the plaster, in my reflection—same brown eyes.

Read by the poet:

Thank you for reading the Poem of the Week!

This week, a poem from the grad school collection I shared last week.

“Stucco and Suture” is a poem about holding on, letting go, and the web that forms when you can’t quite hold on or let go and so waver between instead.

“It’s complicated.” Let’s start there. Look at the line just above that one. It ends with an unfulfilled em dash (—). It hangs over the edge, a loose thread, just like the first and third lines. The separated phrases (such as “A vision— / Train rush.”) suggest sudden displacement or disorientation (“I see you— / Vanish.”). The line reaches out, hand with finger (—) outstretched for touch, but it can’t quite reach. It gets cut off.

Short sentence fragments. Parallel syntax. Repetition. The last three sentences you read are staccato, short phrases that are pronouncedly separated from each other to build emphasis or interpretation. Kinda like jazz solos or a blistering fast rap. These staccato lines begin the poem to establish an industrial, urban tone that escalates into an admission of guilty truth (“How lucky…without you”). The sentences are much longer after that turn.

More Italian: that part of the poem (“lingers— / It’s complicated.”) is called the volta. It is the part of the sonnet where the form and meaning shift in some way. A turn of thought; question & answer; change of pace. The poem’s final sestet (last six lines) is more contemplative and elongated in syntax and meter in this way.

All of these elements are meant to be pieces being “sutured” together in “Stucco and Suture.” Like the speaker’s family and the memories of a “stucco” suburban life, the poem puts itself together.

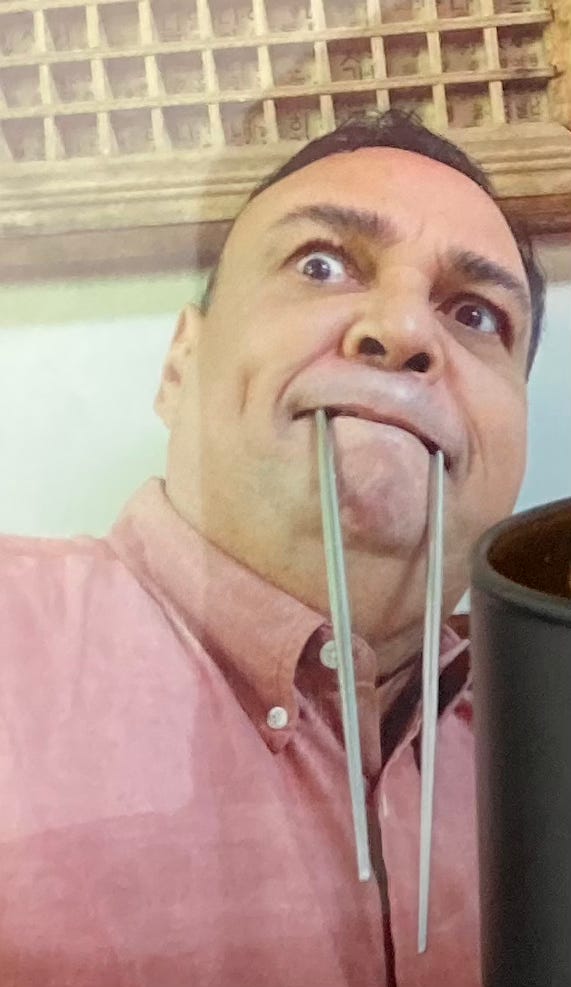

Lastly, this poem is about (and maybe for) my dad. There aren’t too many photos of him in the last few years he was around, but luckily I still have him going walrus-mode. His birthday is coming up, so here’s to the big guy! <3

See you, Ricky